The UK Government’s “Extract” System: Bringing Clarity to the Planning System

A Planning & Heritage Consultant’s View

The UK government’s integration of Google’s Gemini model through the “Extract” system marks a significant technological step forward in planning decision-making. This is an exciting step, after all, AI yields so much potential. But this isn’t a story about AI revolutionising the planning system. It’s a story about applying research, development, and real tools to a critical, long-standing problem; automating the conversion of mountains of old paper maps, PDFs, and scanned documents into structured, usable digital data.

The overarching aim? To substantially speed up the processing of the roughly 350,000 planning applications submitted annually in England.

As everyone working in planning already knows, there are decades’ worth of essential information such as site boundaries, technical drawings, policy maps, and conservation area boundaries held only on paper, in scanned PDFs, or on legacy microfiche. This presents a fundamental barrier to modernising the planning system. Councils possess years of valuable records, but these cannot be easily searched, accessed, or integrated into modern workflows.

The Government has stated:

“Extract will make it easier, faster and cheaper for councils to digitise their historic documents and maps, moving key records out of the filing cabinets in the basement and PDFs on file and into the hands of planners, developers, software providers, policy-makers and the public to unlock development and build more homes.”

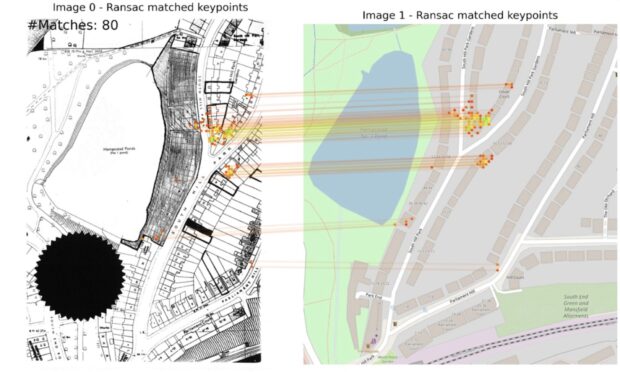

Extract identifying Ground Control Points to georeference the old map. Image created using OpenStreetMaps.

So, What Does This Mean for Planning & Heritage Consultants?

The digitisation of historical planning data presents several key opportunities. Foremost is the enhanced accessibility and analysis of information. Previously challenging to locate, historical data, such as historic planning records containing valuable assessment information, could become more readily available. This improved and easier access will enable more comprehensive initial assessments of sites, including those which are within a sensitive heritage context.

Furthermore, the acceleration of initial planning reviews would be a notable advantage. A reduction in the time required for councils to obtain important site-specific information means that consultant teams may receive pertinent information earlier in the project lifecycle. This earlier access can enable proactive identification of potential concerns, facilitating the overall project timeline and reducing the need for late-stage amendments.

Accessible, digital records may also provide the opportunity for improved stakeholder engagement with local planning authorities, and other stakeholders, ensuring that all planning considerations are adequately addressed in development proposals.

Finally, a potential outcome is a reduction in administrative burden for local authorities. If councils dedicate less time to manual data conversion, resources could be reallocated to other aspects of planning review. This could, in theory, allow for more focused engagement on complex matters that necessitate human expertise and nuanced understanding.

Challenges and Considerations

Despite these opportunities, the introduction of AI into this domain also introduces a series of challenges that require diligent attention.

A primary concern is the potential for decontextualisation. While Extract can digitise content, the inherent context embedded within historical planning documents, such as the specific context behind a handwritten note or the implications of a particular alteration on a historic map may be difficult for AI to fully interpret.

Interpretation relating to the historic environment in particular, relies on understanding these subtle historical layers, and a purely data-driven approach risks overlooking critical contextual information.

The accuracy of AI interpretation is another crucial factor. While the Gemini model’s capability to process “blurry maps and handwritten notes” will prove invaluable, the precision of its interpretation will be paramount. Any inaccuracies in the digitisation or interpretation could lead to erroneous assumptions.

A broader consideration is the risk of reduced human scrutiny. The efficiency gained through automation could inadvertently lead to a perception that less direct human oversight is required. While AI can serve as a powerful tool, it cannot replace the experienced judgment and critical analysis essential for thorough assessments.

Lastly, integration with existing information systems will be vital for the full utility of this new digital data. For the information processed by Extract to be maximally beneficial, it must look to interface with established resources, such as the National Heritage List for England and local Historic Environment Records. Without this interoperability, the newly digitised data risks remaining in isolation, limiting its practical application for heritage and planning professionals.

In conclusion, the UK government’s initiative to integrate AI into planning processes has the potential to represent a significant technological shift. For planning & heritage consultants, this means faster access to critical data, earlier insights into site-specific constraints, and improved collaboration with authorities. However, it also necessitates a rigorous approach to ensure that efficiency gains do not compromise the integrity of the data. The effectiveness of Extract, from a heritage standpoint, will depend on its ability to integrate with systems like the National Heritage List for England and local Historic Environment Records, ensuring the digital future doesn’t overlook the past.

Bethan Weir, Director